Why are the French the most skeptical about COVID-19 vaccines in the EU?

Words by Anaïs Ronchin

France became the birthplace of modern immunology when Louis Pasteur created a vaccine for rabies in the 1880s. This vaccine proved to be so effective that people bitten by rabid animals came from all over France and even from abroad to be vaccinated at his research facility in Paris, which would be transformed into a vaccination clinic and teaching center for this new field of science. However, despite this rich scientific history, contemporary France is experiencing the lowest levels of trust in vaccines in the world.

According to the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor, a report which measures how people think and feel about science and health, one in three French citizens doubt the safety of vaccines. This was the highest amount of vaccine skepticism expressed out of the 144 countries in which the survey was conducted.

Unsurprisingly, distrust in vaccines has peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic. In November of last year, a study revealed only 54% of French citizens would get vaccinated against the virus if a COVID-19 vaccine were readily available. Out of the 15 countries studied, France has the lowest result, ranking below India (87%), the United Kingdom (79%) and the United States (64%).

As COVID-19 vaccines become increasingly available across the EU and France continues to roll out its vaccination strategy, it is more important than ever to understand how French people feel about the vaccines and who they trust for information.

Although center-stage during the COVID-19 pandemic, France’s vaccine hesitant and anti-vax movements are not new

The history between French people and vaccines has been troubled since their creation in the 1880s. Even Louis Pasteur was heavily criticized by associations defending animal rights, polemists accusing him of wanting to make money and doctors skeptical of his new techniques. Indicative of how the general public viewed Pasteur’s research and efforts, the scientist was depicted on the cover of a satirist French magazine.

Even before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, waves of outcry arose in 2018 when the Ministry of Health made eleven vaccines compulsory for newborns, up from the previous number of three. Hesitant parents denounced the high number of vaccines, citing unfounded theories linking vaccines to autism and other diseases, all the while arguing against their general efficacy.

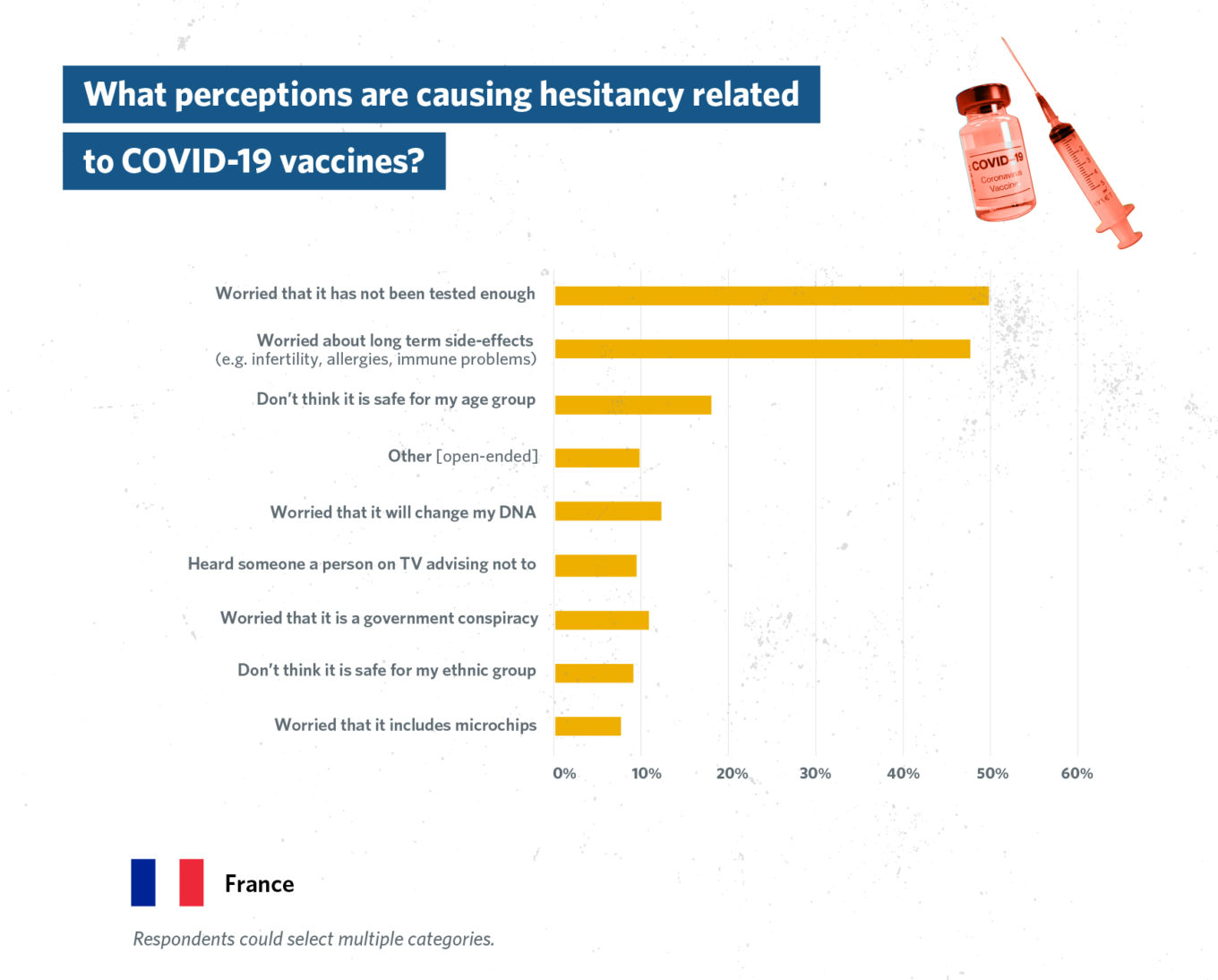

Fast forward three years and you’ll hear the same arguments being rebirthed against the COVID-19 vaccine. After presenting our respondents with a multiple-choice lists of reasons they would refuse a vaccine, we found 50% believe there has been a lack of testing, 48% are concerned about side-effects, 12% are worried it will change their DNA, and 8% are anxious about microchips. Concerningly, 11% of all respondents indicated a belief that the vaccine is a government conspiracy.

What is interesting in France is that anti-vaxxers are not relegated to the sidelines. On the contrary, they are given attention in the media, which usually try to debunk myths related to their theories. As such, it is not surprising to see anti-vaxxers being included in debates and interviews on prime T.V shows or in the mainstream press.

What is interesting in France is that anti-vaxxers are not relegated to the sidelines. On the contrary, they are given attention in the media, which usually try to debunk myths related to their theories. As such, it is not surprising to see anti-vaxxers being included in debates and interviews on prime T.V shows or in the mainstream press.

This approach is double-edged. While it allows experts to immediately refute anti-vax arguments and spread reliable information, it also gives conspiracy theories incredible visibility. For example, clips from a 3-hour long documentary entitled ‘Hold-Up’ supporting the idea of a global conspiracy related to vaccines was widely shared on prime TV and radio shows, including in most read newspapers. This documentary, which featured prominent political figures, including a former Minister of Health (who has since distanced himself from the documentary), alongside researchers, healthcare professionals, hospital directors and sociologists, reached 6 million views in a few months.

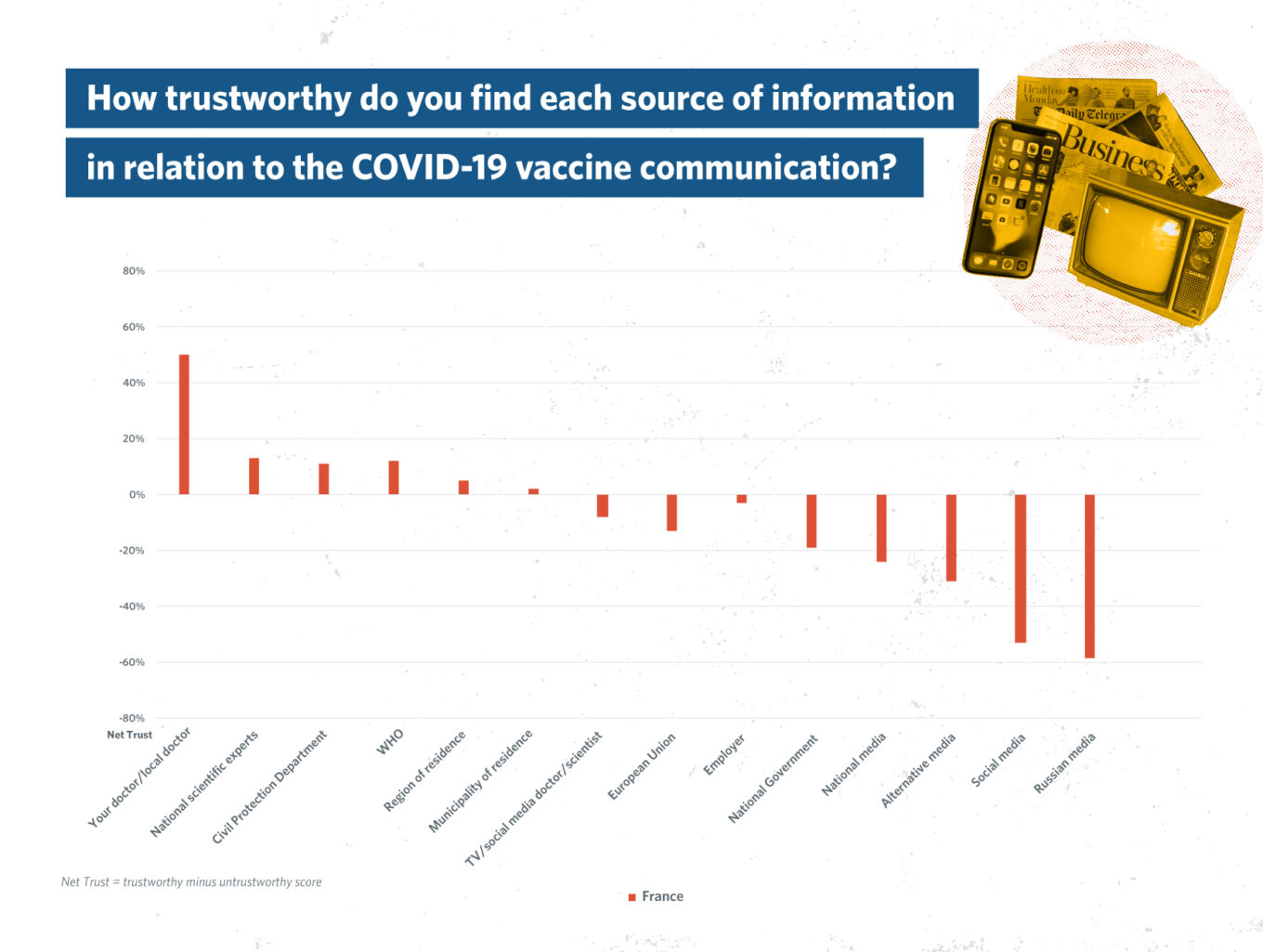

French citizens do not trust their government for vaccine related information, preferring input from their local doctor

When asked to rate their trust in a number of sources for COVID-19 vaccine information, we developed a net trust score equaling responses indicating trustworthiness minus responses indicating distrust. The top three scores for net trust in France were local doctors (50%), followed by national scientific experts (13%) and the World Health Organization (12%). In contrast, governmental sources of information received negative levels of net trust: the national government (-19%), the European Union (-13%) and national media (-24%). Across the four markets surveyed, these were the lowest levels of trust expressed for these categories.

These results should not come as a surprise. Vaccine hesitancy in France is rooted in a deep political distrust nourished by a few, yet memorable, controversies involving vaccines since the 1990s. When 250 patients were diagnosed with multiple sclerosis following a Hepatitis B shot in 1994, the French government was forced to stop the vaccination campaign; even when studies showed that there was no link between the disease and the vaccine (only one of twelve studies showed a connection), it was already too late.

And controversies kept coming. In 2009, the government overestimated the spread of the H1N1 epidemic and ordered too many vaccines, distributing only 6 million doses and incinerating 19 million. The total cost of the debacle was €670 million. In 2013, a lawsuit was filed against a French pharmaceutical company as patients vaccinated against human papillomavirus denounced heavy side-effects to their nervous system. The case was dismissed when the court ruled that evidence did not link these issues to the vaccine.

Even as the French government made sure the misinformation was addressed in each debate through further research and concrete evidence, the damage had already been done.

In this respect, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented a scandal no different than that of its predecessors. French citizens have received contradictory information from the government – masks are ineffective, stocks for masks and gloves are high enough, citizens will never have to buy their own masks, lockdowns will not be necessary – which has changed frequently and has sometimes seemed to even go against scientific advice. As a consequence, the already fragile trust in the French government has been sinking ever since.

Communicating responsibly about COVID-19 will help encourage vaccine uptake

What can be done against vaccine hesitancy? In France, the burden of past scandals, political distrust, fear and visibility of conspiracy theories render this problem extremely difficult to tackle. Even more so, a study by the Jean Jaurès Fondation showed that there is no specific profile of antivaxxers: they vary in age, use of social media, and socio-economic background. They do, however share a common ground as they typically identify with populist parties: voters of the far-right and far-left political parties, according to the Fondation, are more likely to be anti-vax than the rest of the French.

Now is the time for better communication. The French governments has a double mission to be fulfilled urgently: ensure that information about vaccines is reliable and restore trust with its citizens. This comes with stepping-up communication across the board, not just when new lockdowns are being announced, all the while remaining as transparent as possible and showing its crisis management skills. Because at the end of the day, there is no point in having safe and efficient vaccines if nobody is taking them.

Check out our full report for more insight!

-

Emma leads FleishmanHillard EU’s Health and Lifesciences team, providing public affairs and corporate communications sectoral expertise to clients. Emma has worked on high-profile pieces of EU health legislation, including the General Pharmaceutical Legislation and EU-wide HTA, and has a particular passion for supporting clients to...

Find Out More

-

Are you fit for 2024? Communicating in a year of change

February 27, 2024

-

Why Europe needs a water resilience strategy

February 8, 2024