SEPA migration - A milestone for the single market. But what’s next?

- What has been achieved

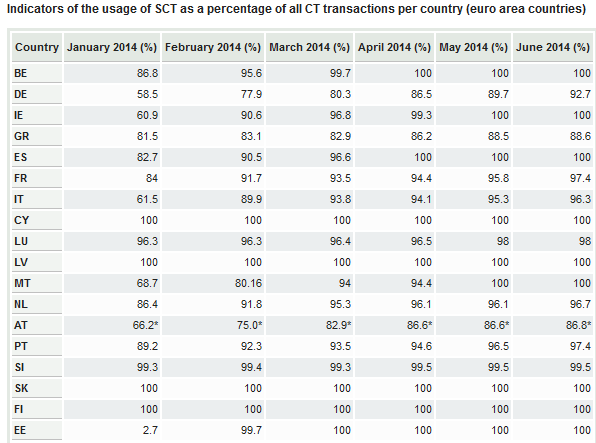

Whilst attention over the past months has focussed on the high politics of institutional change, continuing efforts to reboot the economy and attempting to nudge some order into the EU’s eastern neighbourhood, a quiet evolution has taken place in the euro payments system. Originally planned on 1st February 2014, the extended deadline of 1 August marked the date for all Eurozone payment transactions to migrate into SEPA compliant formats, completing – in the words of the ECB – “one of the largest financial integration projects in the world”[1]. In simple terms, it means all payment transactions will have to be handled in compliance with a set of standardised rules, of which the IBAN/BIC system is the most noticeable. The extension of the deadline was necessary to avoid severe disruptions in the EU payments market as not all market participants were ready to use SEPA standards by 1st February. The table below shows the strong compliance efforts accomplished over the first half of the year.[2]

Source: European Central Bank

It’s worth clarifying that whilst SEPA deals with payments made in Euro, SEPA also covers the broader European region. In fact not only are all EU member states part of SEPA, but also Norway, Iceland, a series of microstates (Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Andorra), and even Switzerland. By way of derogation, market participants in non-Eurozone countries have until the end of October 2016 to ensure full migration – while certain “niche” products also enjoy temporary exemptions across the EU.

While this migration is in many ways a technical achievement rather than a political one, the idea of SEPA is deeply rooted in the idea of the Single Market, making this largely unnoticed event one to remember for the spiritual descendants of the likes of Jacques Delors.

2. What is SEPA, and why is it important for the Single Market?

The “Single Euro Payment Area” project is a natural outcome of the creation of the Euro, and is an offspring of the 2000 Lisbon competitiveness strategy. The logic is compelling: creating a single currency and supporting a series of natural “spin-offs” of the Euro will tear down the remaining barriers to cross-border trade and investments and – once these forces are unleashed – will result in higher levels of growth. The hope was to not only create a SEPA but a fully integrated financial system and economic space, where borders for financial markets would be a thing of the past.

From this perspective, it is undeniable that SEPA is one of the most successful outcomes of the Euro project. In essence, it standardises Euro denominated transactions in the SEPA, which – as mentioned before – is broader than the Eurozone. This standardisation goes beyond the standardised use of the IBAN/BIC scheme, but sets out a complete standardised rulebook governing processing, clearing & settlement. It is a classic example of reducing friction costs which most economists and policy-makers will only applaud. Indeed, an economic analysis commissioned by the European Commission to PWC, estimates the benefits of a “fully embraced” SEPA at around €22 bn in yearly savings resulting from price convergence and process efficiency.[3]

2.1 Benefits and limitation of SEPA: A Euro d(en)ominated project

The benefits of the SEPA are undeniable, not in the least from a very practical perspective. However, there are some remaining limitations that remain present even after successful migration.

SEPA marks practically full standardisation of pure Euro transactions, which for consumers making cross-border transactions within the Eurozone means that – in theory – they should be as easy/fast/reliable as domestic transactions. This is important because in the past, despite the introduction of the Euro it could have still proved challenging and time consuming for interbank and/or cross-border payment transfers, because of different formats of bank account numbers, standards, clearing process, etc. Under the SEPA project, from now onwards, a French bank account holder should be able to conveniently make daily payments across the Eurozone. She can just go online to pay monthly rents for her apartment in Paris and book a beach house on Fuerteventura for holidays – two experiences that will be almost identical procedurally – in a couple of clicks, without additional paper forms to fill in, phone-calls to make or long-queuing during visits to the bank.

From an EU Single Market point of view, the beauty of a fully endorsed SEPA system is that it applies to all euro payments made in the SEPA area, regardless of whether the counterpart’s account is denominated in Euro. However, this is not to say that SEPA is the perfect solution. For Euro to non-Euro transactions, whilst they also enjoy the benefits of SEPA standardisation, there are some limitations due to the risk and transaction costs associated with currency conversion. This is indeed an inherent limitation of SEPA, as at this point, 14 different currencies circulate in the single payments area.

Euro-domination manifests in the governance of SEPA, as the newly established European Retail Payments Board (ERPB), an engagement platform set up to provide input into SEPA related policy issues, is firmly rooted within the ECB, which has a strong mandate for governing the SEPA area. The ECB also oversees the SEPA compliant credit and debit schemes, while it also plays an important role in payments settlement through Target2. For obvious reasons the ECB is, of all EU institutions, the most euro-centric.

2.2 Ongoing project to build a single payments market: looking beyond SEPA migration

Some other EU legislative proposals touch on the fundamental idea of SEPA, i.e. promoting a single EU payments market. EU has recently adopted rules with the objective to make it easier for citizens to switch/open payments accounts in different Member States. This initiative, which originated from the concept of social inclusion, can also find roots in single market logic, although it is not without industry concerns around some practical implications on, for example, fighting financial crimes. Further, the review of the Payment Services Directive currently negotiated is crucial in improving consistency between national rules as well as enhancing competitiveness and security. One of its main aims is to bring new payment services providers within scope of the EU supervisory framework to ensure level playing field regarding security and consumer protection. The more politically controversial proposal to regulate interchange fees between banks is also embedded with the concept of pushing for a more competitive and integrated payments market. Ongoing debates between policy-makers and market participants shows that, in the path towards a more integrated and competitive payments market, it isn’t necessarily easy to draw a clear line between unjustified high transaction costs and a proper profit generating system to ensure the provision of quality services and encourage innovation.

While SEPA experiences some limitations within Europe, it probably isn’t entirely foolish to suggest that (parts of) the SEPA rules could be expanded across the globe. Although SEPA is an EU project, one of its components, the IBAN, stands for “International Bank Account Number”. While first developed by the European Committee for Banking Standards, it was later picked up by the ISO, the International Organisation for Standardisation . Today, aside from SEPA, only a few other jurisdictions have implemented the IBAN/BIC model, amongst which are Turkey and Brazil. Though global standardisation has not always been successful – think of the last time you’ve tried to charge your laptop abroad – in several cases, the EU has been a decisive pioneer in pushing for global standards.

Martin Bresson, Mandy Shi Lai and Marijn Swinters

[2] This table only shows the migration rates for credit transfers. Numbers on the other two relevant categories, direct debit transfers and card payments, showcase a similar trend. More info on: http://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/sepa/about/indicators/html/index.en.html

Find Out More

-

The EU year of change: Act 2

June 13, 2024