Last week the question over ageing populations in Europe re-emerged following the release of UK census results, which showed that citizens over the age of 65 now make up almost one fifth of the population, the highest figure ever. The increase in over-65 population is occurring alongside a decline for those of working age, which raises fears over long-term economic stability.

This trend is causing increased pressure on overburdened healthcare systems to a degree that is threatening the long-term sustainability of health and social care provision in the UK. But the UK is not alone in this issue, it’s one that permeates across Europe. Governments are being forced to take the difficult choice between increasing the taxation burden on the working population or scaling down on the welfare state.

What does it all mean for European citizens and can inspiration to combat the issues be drawn from elsewhere?

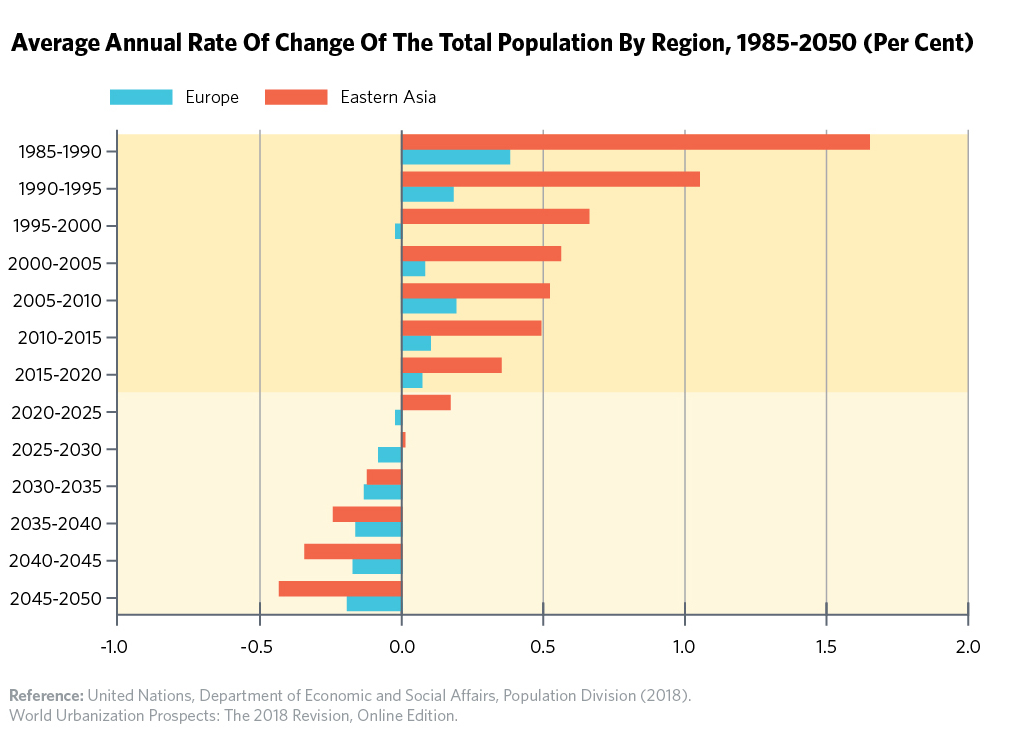

Alongside the ageing population, UN projections suggest that some of the core Western European countries such as France, Germany and the UK will start to see a population decline in the next 10 years, with myriad determinants largely rooted in increasing pressure on young workers and the growing cost of childcare.

This is already leading to governments spending an increasing portion of their purses on the provision of healthcare, and other social policy. Governments in Europe have looked to combat this by shifting focus to the use of new technology to combat the rising costs, but little has been done to prevent the acceleration of the falling birth-rate which is driving this problem.

In Eastern Asia, however, population decline, and the ageing population, are core concerns of government. Large population growth in the 20th century is being followed by a sharp decline in the birth rate which has required more urgency from policymakers. This has meant that governments have been more proactive in the introduction of policy measures to combat this decline both through improving the birth rate and modernising services.

Potential policy levers will likely see countries look to have a clear and defined long-term strategy aimed specifically at increasing the birth rates. The French government are currently drafting a National Action Plan on Infertility, which is yet to be published, but further action at European level has been limited.

In Asian countries, however, their populations are projected to start declining at a much faster rate. This has led to more proactive policies to alleviate this. The ageing population is a clear priority in China, where the government last year released a plan for “a long-term balanced population by 2035” and in which the ageing population regularly features in the media.

While there are clear differences culturally and politically, the ultimate issues that are causing the growing concern are largely similar, with action predominantly focused on creating a better environment for couples to have children. In addition, some of the major policy determinants are similar, with growing inequality in access to healthcare and the need to ensure the long-term sustainability of overburdened healthcare systems.

Reluctance to increase spending has led to multiple policy levers being used. In Japan and Italy, the government has piloted handouts to new parents to assist with healthcare but ultimately, this has been received as a “gimmick” which recognises the broader concerns but fails to address the long-term determinants of the growing issue.

China has been more proactive in looking to ensure a society in which work pressure and childcare cost does not serve as the main obstacle for young couples to decide to have children. While some of the issues on cost were more prominent, particularly in Chinese cities, where the government has focused on reducing education costs and encouraging shorter working hours. On childbirth specifically, the Beijing local government is currently trialling government funded IVF for couples suffering with infertility, which has also been driven-up by the same societal issues along with couples choosing to have children later on.

Ultimately, the restricted funding for healthcare makes drastic policy changes at a national level unlikely, so proposals for the provision of free childcare will likely be deemed unaffordable. Despite this, inaction on these societal issues that are core determinants of birth rate decline will likely impede further policy measures from having a desired impact. This means the combination of having a long-term plan which focuses on meeting core targets, while simultaneously introducing policies that create an environment which makes caring for children more affordable for young families, will be the best way to avoid the decline.

Find Out More

-

Generative AI is changing the search game

May 8, 2025

-

The challenges facing Europe and European leaders at Davos 2025

January 24, 2025