When Jean-Claude Juncker took office last year as President of the European Commission he claimed that Europe had a problem – it was chronically under-investing in its critical infrastructure. The long lag in economic growth following the financial crisis and the fiscal pressure felt by most European countries since have contributed to an investment gap of up to €370 Bn below Europe’s current potential – compounding the economic malaise of the continent and reducing, in turn, Europe’s foundation for economic growth in the future.

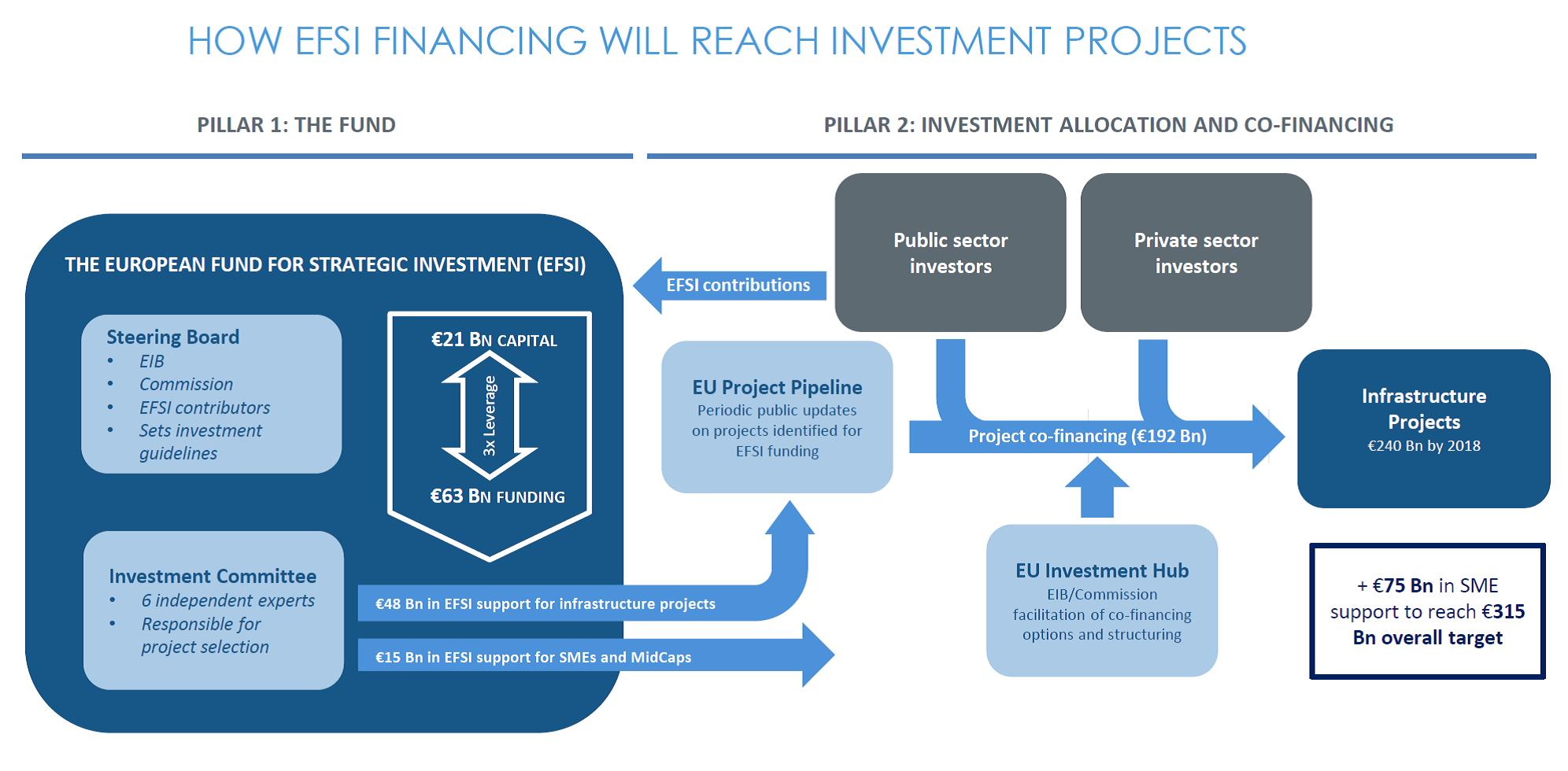

Luckily however, Juncker didn’t just identify the problem but made finding a solution to it the headline priority of his first year in office. Enter the EU Investment Plan (#InvestEU for you Twitter addicts, and better known as the ‘Juncker Plan’) which proposed to mobilize €315 Bn in investment finance over three years along with a range of initiatives to improve the general investment environment in Europe. The centerpiece of the Plan was the creation of the European Fund for Strategic Investment (the EFSI) which would work within the European Investment Bank to leverage and direct the seed capital for the €315 Bn target towards the most efficient projects Europe has to offer.

We might then all have a cause to celebrate this week, as EU Finance Ministers reached a quick agreement on the structuring legislation for the EFSI yesterday. But before anyone uncorks the champagne, we should take stock of the obstacles the Juncker Plan still faces – as the road between yesterday’s agreement and filling Europe’s yawning investment gap is a very long one indeed.

Challenges Ahead for the Juncker Investment Fund

It is firstly worth noting that the political process to establish the EFSI Investment Fund is not actually complete. European Member States, having now reached an agreement, will now have to negotiate with the European Parliament on a common position before EFSI can enter European law – something which needs to happen before the summer break (this is, by all means, an extremely tight timeline for the European legislative process).

The bigger challenges, however, might lie outside of the political process, as it’s a very poorly kept secret that the European money mobilized for the Fund is nowheres close to its €315 Bn target – it’s actually just €21 Bn.

All the rest has to come from leverage and co-investment, which can’t be done by legislative decree.

The first step will be for the EIB to leverage the €21 Bn three times to €63 Bn. This is, of course, very achievable for an institution with the expertise and creditworthiness of the EIB.

The trickier bit is co-investment. In short, the remaining funds (fully €252 Bn) will have to come from public and private investors who decide to invest alongside the EIB in specific projects supported by EFSI (a process that will look something akin to the graphic below).

To give you an idea of the scale of the challenge, France and Italy, Europe’s second and fourth largest economies respectively, just this week committed to co-investing €8 Bn each in EFSI projects undertaken in their countries. That still leaves another €236 Bn of funds entirely unidentified at this stage.

What about the private sector?

It’s clear enough to everyone involved that the private sector is going to have to step up and take advantage of historically low interest rates by investing more in infrastructure. But how can we convince them to actually do that in time?

The answer to this is not so much in the Fund itself, but the broader Plan. You didn’t forget that the Plan was bigger than just the Fund, did you? Crucially, it is.

The ‘Juncker Plan’ includes a range of initiatives meant to substantially improve the environment for infrastructure and other investment in Europe. This includes creating a European Infrastructure Pipeline and Infrastructure Advisory Hub, both meant to enhance the transparency and investability of infrastructure as an asset class for large institutional investors (think pension funds and insurers).

Initiatives like the infrastructure pipeline are crucial innovations as one of the biggest roadblocks for private sector investment in infrastructure has been the lack of deal-flow and past performance data in many countries. This is mostly the case because infrastructure is traditionally seen as a public good with no steady record of private sector involvement in funding its creation. A European-level pipeline of identified projects would help investors plan their investment allocations over time and give them more information to consider increasing their exposure to infrastructure in general.

This maybe sounds easier than it will actually be. In practice, private investors often plan their investment allocations years in advance and have to balance those decisions within a diversified strategy that relies on carefully made decisions about risk appetite and the financial instruments used for investment.

In this context, it’s important that public sector officials develop a strong understanding of how private investors make their decisions and what they need in order to co-invest in EFSI-type projects. The skepticism demonstrated by some EU countries over the infrastructure pipeline (now made optional by the Council’s agreement for countries to participate in) is an example of just such a disconnect that could risk the Plan’s ability to attract private interest.

Overall however, the Juncker Plan has been proposed by the Commission and initiated into the European legislative process in record time. The need for such an initiative is clear, and this has been reflected in the high priority attached to it by almost all Member States and political groups in the EU. The quick process of establishment though, highlights the need to make sure we get things right the first time. Recognizing the role the private sector will have to play in this and considering how best to ensure that this actually happens is therefore perhaps as urgent as the Plan itself.

Find Out More

-

Generative AI is changing the search game

May 8, 2025

-

The challenges facing Europe and European leaders at Davos 2025

January 24, 2025