Unlike the hurley-burley of these first days of institutional activity, August was a fairly quiet month in Europe – far set from the troubles and tensions of previous summers and the frenzied preoccupations over economic collapse. This year, Brussels emptied itself of tired civil servants, who trudged, nostalgically back to their homelands, and European capitals were filled with an unusual sense of calm – a pause between political seasons.

However, not all states were blessed with calm and warming summer breezes. A tempest was slowly brewing in Portugal where, on 4th August, the crisis hit the second largest national bank (by total reported net assets) and the ship was sunk. Banco Espírito Santo (BES), with €80.2 billion in assets and €36.7 billion in customer deposit, disappeared almost overnight.

Leaping into action, the Central Bank of Portugal resolved[1] the bank by separating BES’s sound business activities from toxic and dangerous assets thus creating a ‘bridge bank’. The “good bank” is now supported by €4.4bn from the Portuguese state, while the “bad bank” has kept the unfortunate, but appropriate, name of Espírito Santo (i.e. the Holy Spirit, but also the name of the proprietor family) and will be wound down in due course.

It seems inconceivable that only three months after Portugal’s victorious emergence from the bail-out troika (European Commission, ECB & IMF), with all that it entailed in the form of deeper scrutiny and attention, public money is still being used salvage the remnants of a banking disaster and to protect investors from ample losses. After years of Banking Union negotiations and reassurances to markets, policymakers and regular sunbathers, will all be lost?

Let’s take a look at the bigger picture – the who’s and the what’s.

With a century and half of history at its shoulders, the group to which Banco Espírito Sancto belongs, has progressively grown to become a vast empire, held in majority by the descendants of its founder. In the process, the group has expanded across borders, covering different countries and various sectors from banking to tourism and construction, thus becoming a common name in Portuguese households, the local Rockefellers.

However, this wealth of historical heritage brought little wisdom with it. When a new executive team took over BES in July, it soon discovered that the former administration had hid from regulators and the world, a €1.5bn hole in its budget, generated in the first-half of the year (50% of what BES has lost in total) – a situation far from that expected for a bank held by Portugal’s richest family.

Advice given by BES’s external auditor, to counter over exposure to conflicts of interest within the group, was ignored and proved to be fatal. Today, it seems clear that the undetected operations were repackaged by a financial intermediary partly owned by BES, in order to keep them off the balance sheets.

Record losses meant that BES’s solvency ratios fell below the regulatory minimum required to receive ECB funds, and the Bank of Portugal was confronted with an urgent choice – whether to mount a rescue plan, protecting senior[2] debt holders, or allow BES to orderly fail by applying soon to be implemented Banking Union rules.

Overnight, the Bank of Portugal decided to undertake a sort of hybrid rescue plan, mixing both bail-in and bail-out tools.

Bail-out tactics: In order to properly capitalise on the new bridge bank, the Portuguese Resolution Fund was given €4.9bn, of which €4.4bn deriving from the Portuguese State – an amount of money that tax payers will not recover if the selling price of the bank remains lower than the amount lent.

Bail-in tactics: The bridge bank system implied that all the junior bond holders and most shareholders whose assets had been isolated in the “bad bank” would endure severe losses.

If the procedure was completely legal, it was still in grey area. Had the Governor of the Bank of Portugal followed new EU rules on bail-in processes, senior debt holders and large depositors would have been part of the haircut too. As from the 1st January 2016, preserving them will no longer be possible.

Reasons for the choice of a hybrid system are varied and could be seen as a reluctance of regulators to go against the European conception of senior bond holders being implicitly backed by the state, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves and jumping to conclusions.

Let us now look at the “so what’s”.

All signs (or at least those we’ve chosen to look at for this blog) show that the whole operation was a success. And an admirable one at that! Less than a month after the bank was wound down, Portuguese 10 year bonds have reached their lowest point for debt emission in 2014 and Portugal is experiencing growth again for the first time in four years (EC figures).

Source : http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/GSPT10YR:IND/chart

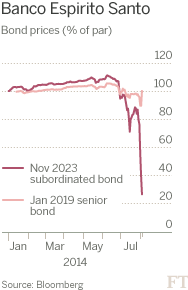

Moreover, being attached to the new, “good” bank, senior bonds barely shifted, while junior bonds have plummeted, illustrating a sense of trust in the path chosen by the Bank of Portugal.

Source: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/691f64ba-1bbb-11e4-adc7-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3CG611CPN

Data therefore suggests that financial markets have bought into the “ring-fencing” tactic, and the risks associated to BES senior bonds will not threaten other banks or the rest of the economy.

On that happy note, but in the slightly gloomier spirit of autumn, an underlying question remains – whether this well-orchestrated resolution and the resurrection of the BES banking group, would have complied with the soon-to-be rules and principles of the Banking Union.

Quite frankly, the answer is – not entirely – or at least, not as shown above. Contentious areas are capital requirements, supervision, bail-in vs bail-out systems (let alone question of whether funding in the Single Resolution Fund was or ever will be sufficient) and, the true moratorium – whether senior bond holders understand the need to adapt their behaviour as from 2016 when the EU-wide rules on bail-in kick-in.

But we’re not going to ask the big question – whether the Banking Union has really changed anything. We’re not! Because of course… it has! So don’t be so gloomy. Go catch the last sunlight, go chase rumours about the next Commission and let summer events be summer events and… have faith!

By Martin Bresson, Claire Bravard & Alessia Mortara

[1]When a regulator decides to close down a bank that because it failed.

[2] Bond holders that will be will be paid back before junior bond holders and shareholders if the bank goes bankrupt (and if there is enough money left)

Find Out More

-

Generative AI is changing the search game

May 8, 2025

-

The challenges facing Europe and European leaders at Davos 2025

January 24, 2025